When I started my dissertation research at Columbia, I discovered an exciting resource that displayed primary sources printed in England (or English) between the years 1475 and 1640 in their entirety. No longer dependent on transcripts or facsimiles which simply replicated features of the text in modern type, nor on expensive, intensive research trips during summer vacations, I was able to look at photographs of the works and see “exactly” how they appeared when first published, whenever I needed. Moreover, I could even make reproductions of the pages without writing librarians to request photographs of rare and fragile works in their special collections. All I needed were stacks of dimes and patience.

This resource, known as “Early English Books,” emerged in 1938 as the crown jewel of Eugene Power’s growing publishing company University Microfilms International. Power based his project—to photographically duplicate early British codices–on Pollard and Redgrave’s 1926 Short Title Catalogue of Early English Books, an annotated list of “English books” produced between 1475 & 1640 and housed in British collections. These included books printed in England, but also books printed elsewhere in English between those dates. “English” thus signified both the language and the nationality of the books, an unstable if ideologically productive category, then and now. While Pollard himself warned readers to take the collection as “a catalogue of the books of which its compilers have been able to locate copies, not a bibliography of books known or believed to have been produced” in the period, the list has always projected completeness through its size and relative documentary consistency.[i] Originally published in two volumes by the Bibliographical Society, a second edition with additions and corrections in three volumes took several decades to complete, emerging in 1991. In both, texts appear listed alphabetically by author with its “short title,” size (quarto, octavo etc), publisher, and date of publication (and /or date of entry in the Stationers’ Register). Occasionally, the editors included other useful but inconsistent bibliographic features of the text like typeface or two-color printing. Crucially, they also provided abbreviated lists of the major libraries in which copies could be found: these were expanded to collections outside of Britain (primarily English-speaking former colonies) with the second edition.[ii]

I knew of Pollard through his work as a “New Bibliographer” developing would-be scientific methods of textual scholarship in order to better chart the printing and production of Shakespeare’s plays, particularly the variants between Quarto and Folio editions. However, until this infrastructure project, I had no notion of Power or how the microfilm collection came about. Having turned to the STC in response to the limited holdings of early printed books in US collections, on the eve of WWII, Power convinced the institutions listed there to allow the photographing of the works as a safeguard against restricted transatlantic access and potential risk to libraries from the coming war.[i] As fears of damage to European collections grew, so did Power’s support—from the American Council of Learned Societies to the Rockefeller Foundation and eventually from U.S. intelligence departments—both “to bring microfilm copies of source materials from all parts of the world to [America]” so that “the centre of learning would shift to the United States” and increasingly to copy and send documents obtained by the OSS back to Washington. During the conflict, Power thus marshalled high-quality photographic instruments being used for wartime military reconnaissance for “Early English Books.” In turn, with its experience and contacts, Power’s company successfully continued reproducing important government documents and obtaining lucrative military commissions well into the Cold War.

Holed up on the top floor of Butler library, ironically just down the hall from Special Collections where I might have looked at some of these works in their material instantiations, I knew nothing of the military-intellectual complex that made this research possible. I focused mostly on the rolls of film, the microfilm machine reader, and the quirks of the mechanical system. The elaborate procedure for finding a book required first identifying in the printed STC the catalogue number of a specific work, and then consulting a less impressive UMI paperback that cross-listed the STC number with the number of the relevant microfilm reel. Each reel contained multiple texts and after laboriously threading the film onto the stationary reel, I’d speed-scroll towards my desired text, inevitably passing it. After some back and forth, however, the correct black-and-white images would thrillingly emerge, revealing blank pages, catchwords, prefaces, all the telling material not included in prior facsimiles. One could even save and take home a particularly interesting recto and verso,: inserting a dime in the machine’s side would produce an inky greyscale print of the viewer screen. Finally, one would rewind the film, retrieve its protective manila cuff, and place it on a cart for return to the massive metal file cabinets in the adjacent rooms. These storage units, the uniform style of the reels, and their little catalogue boxes, gave the STC a further sense of completeness, even as one discovered the gaps in the collections. In this way, New Bibliography’s positivism found support in the no-longer-futuristic promise of mid-century duplicative technologies.

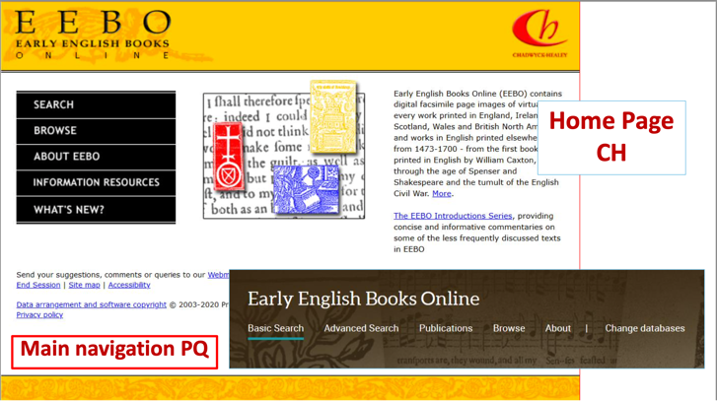

On returning to the project several years later, to prepare the book manuscript, I found a strikingly different knowledge infrastructure. Xerox had already merged with UMI’s parent company, Bell and Howell, but in 1999 Bell and Howell acquired the Chadwyck-Healey publishing group, which had started as a reprint business and then had moved from publishing research material on microfilm, to CD-Rom, and then to digital platforms. While Early English Books (now EEBOnline) had always been part of the parent company, Bell and Howell (and subsequently ProQuest) used ‘Chadwyck-Healey’ as a ‘brand’ not only for its content but also for its fine-print aristocratic associations. Accordingly, the first online databases for the STC, namely EEBO, had a mixed archaic aesthetic that included snippets of texts with ligatures and woodblock prints. When it retired the “legacy” site, ProQuest retained the serif typeface for the title but pushed the text images into the background and dimmed them, foregrounding an expanded search bar, and links to cross searches with other subsequently acquired platforms. Both the past Chadwyck-Healey and the current ProQuest home pages state that the database contains “digital facsimile page images of virtually every work printed in England, Ireland, Scotland, Wales etc etc,” or, more simply, “page images of almost every work printed in the British Isles”: each misrepresenting their comprehensiveness (particularly as not all the STC works on microfilm have been transferred to digital form, let alone transcribed into searchable text). Nonetheless, the instantaneous access to multiple works, the advanced search engines, the possibility of creating downloadable pdfs and excel sheets of bibliographic data changed not only the number of works that could be examined in a project but the questions that one could ask of them. My book history was forever transformed.

As Bell & Howell turned into ProQuest/Ex Libris, was sold to and then sold by Thomson Reuters, and ultimately became part of ClarivateTM, EEBO has become an ever smaller part of the company’s holdings and attention. Clarivate describes itself as primarily an analytics company: “We pair human expertise with enriched data, insights, analytics and workflow solutions – transformative intelligence you can trust to spark new ideas and fuel your greatest breakthroughs.” As a main provider of “Content Solutions,” ProQuest resides under the category “Academic & Government” with the stated aim of helping “researchers, faculty and students achieve success in research and learning.”[i] Yet, as Clarivate focuses increasingly on providing governments with “trusted intelligence for advanced real-world outcomes” generated through “precise insights from billions of data points ingested and normalized from thousands of sources, enriched with AI” it’s hard to see what value Early English Books will continue to hold for the megacompany. Perhaps Clarivate will retain the database out of nostalgia for and recognition of EEB’s origins in the morally questionable intertwined interests of national, military, and knowledge infrastructures which they both share, albeit technological light-years apart.[ii] If not, will I be forced to return to the Butler microfilm room? Amazingly, it still exists, although one no longer needs dimes.

[i] Mak, Bonnie. “Archaeology of a Digitization.” Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology 65, no. 8 (2014): 1515–1526.

[ii] https://folgerpedia.folger.edu/English_short_title_catalogue

[i] Like Pollard, Power emphasized the limited nature of his compendium: “The collections listed are not complete. Only those portions of particular interest to American scholars were microfilmed” (Power, 1990, Appendix C, p. 385). Cited in Mak.

[i] As with EEBO, ProQuest continues to move many Chadwyck-Healey “legacy” databases to its primary platform. However, some legacy databases have been or “will be sunsetted”—folded into other databases rather than functioning as standalone collections. In extreme cases, for example the “content in the African American Biographical database,” and “Historical Newspapers Online,” the information moves to a different database in which “much of the content from those collection [sic] has been made available in other products.” Without a detailed search, it’s hard to get a sense of what is lost in each of these transfers, but, at least for EEBO, some of the most useful (if inconsistent and idiosyncratic) bibliographic information can no longer be easily, if at all, accessed. Certainly, without access to the print volumes of the STC, users of the database will have little understanding of the group labor, primarily by women, that went into its original compilation, or into Power’s initial projects both bibliographic and military (see Mak).

[ii] “the history of the Early English Books microfilms is entangled with the history of technologies of war (Power, 1990, p. 148). The relationship also worked in the other direction: namely, the earlier success of the STC subscription service put Power in a position such that his business was able to handle copying voluminous quantities of material, and at speed, as required by the federal agencies in their wartime efforts. As a consequence, UMI was able to compete with larger outfits that included Recordak, the subsidiary of Kodak, and even outbid them on military contracts.”